Why shooting stars aren’t stars at all: Understanding meteors, meteorites, and meteor showers |

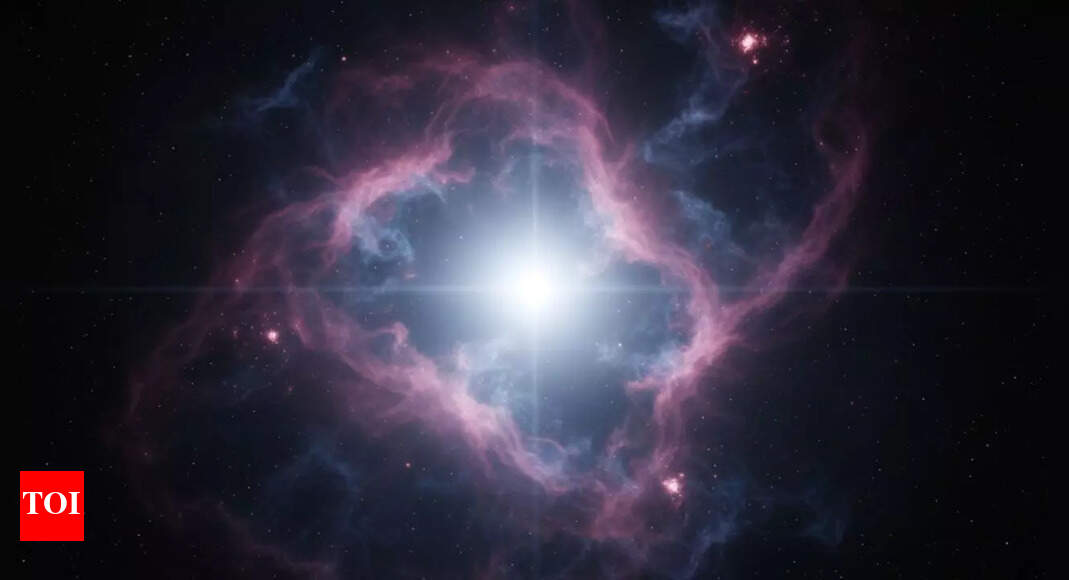

When you look up at the night sky and spot a bright streak of light racing across it, you’re witnessing one of nature’s most mesmerising events- a meteor, often called a “shooting star.” Despite the name, these dazzling flashes aren’t stars but tiny fragments of rock or dust from space. As they enter Earth’s atmosphere at incredible speeds, they burn up, creating a brief, brilliant glow. According to NASA, meteors and meteorites offer valuable insight into the early Solar System, helping scientists understand the origins of planets, asteroids, and the cosmic materials that shaped our world.

Meteoroid, meteor, and meteorite: How they differ and what each one means

Many people use the terms “meteor” and “meteorite” interchangeably, but astronomers make a clear distinction between them. These terms actually describe different stages of the same object’s journey, from drifting in space to burning through the atmosphere and, in rare cases, landing on Earth. A meteoroid is a small rock or particle moving through space, often left behind by comets or asteroids. When it enters Earth’s atmosphere, it becomes a meteor, glowing brightly as it burns up. If part of it survives the fiery descent and reaches the ground, it’s called a meteorite.

So, the “shooting star” you see is not a star at all, it’s a meteor, caused by a meteoroid travelling at immense speed and glowing as it disintegrates in the upper atmosphere.

The fiery descent: What causes a meteor’s glow

As a meteoroid enters Earth’s atmosphere, it collides with air molecules at speeds ranging from 11 to 72 kilometres per second. This immense friction and pressure cause the surrounding air to heat up and ionise, producing a brilliant streak of light — the meteor.Most meteors burn up completely between 80 and 100 kilometres above the surface, long before they can reach the ground. The smallest meteoroids may be no larger than grains of sand, yet their high velocity causes them to flare brightly for a split second.Only a small number of larger objects survive the descent. NASA estimates that less than 5% of a meteoroid’s original mass typically makes it to Earth’s surface as a meteorite.

Meteor showers : When the sky comes alive

At certain times of the year, the night sky seems to light up with dozens of meteors per hour — a breathtaking spectacle known as a meteor shower.Why meteor showers occurMeteor showers happen when Earth passes through a trail of debris left behind by a comet or, in some cases, an asteroid. As our planet’s orbit intersects with this stream of dust and rock, many small meteoroids enter the atmosphere and vaporise almost simultaneously, producing a shower of shooting stars.Some meteor showers are predictable and occur annually because Earth crosses the same debris field each year. Notable examples include:

- Perseids – Active in August, originating from the comet Swift–Tuttle.

- Leonids – Peaking in November, linked to the comet Tempel–Tuttle.

- Geminids – Appearing in December, unusual because they originate from an asteroid (3200 Phaethon) rather than a comet.

Meteor showers are named after the constellation from which the meteors appear to radiate — their radiant point. For example, the Perseids seem to come from the constellation Perseus.

When space rocks reach Earth: The story of meteorites

When a meteoroid is large enough to survive its fiery entry, the remaining fragment that reaches the ground is called a meteorite. These space rocks are invaluable to scientists because they carry the chemical fingerprints of the early Solar System.Meteorites are classified into three broad categories:

- Stony meteorites – Made mainly of silicate minerals, resembling terrestrial rocks.

- Iron meteorites – Composed primarily of iron and nickel metals, often with a shiny, dense appearance.

- Stony-iron meteorites – A mixture of metal and silicate crystals, among the rarest and most beautiful types.

Most meteorites are covered with a thin black fusion crust, formed when their surface melts during entry.

Origins and composition of meteorites

According to NASA, nearly all meteorites come from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. A small number, however, can be traced to the Moon or Mars, identified by their unique mineral structures and trapped gases.These cosmic samples provide insight into planetary formation, asteroid collisions, and even the chemical conditions of the early Solar System.

Common myths and misconceptions about meteors

Despite their beauty, meteors are often misunderstood. Here are some common myths, and the truths behind them:Myth: Shooting stars are real stars.Fact: They are fragments of rock or dust burning in the atmosphere.Myth: Every meteor results in a meteorite.Fact: Most meteoroids completely vaporise before reaching the surface.Myth: Meteor showers drop meteorites on Earth.Fact: The particles in meteor showers are usually too small to survive atmospheric entry.Myth: Meteorites are hot when they land.Fact: Most meteorites cool rapidly during descent and are often cool or only slightly warm to the touch when found.

How to observe a meteor shower

- Choose a dark location far from city lights.

- Let your eyes adjust to the darkness for 20-30 minutes.

- Look at the sky with a wide field of view- no telescope needed.

- Be patient; meteors often appear sporadically.

The best viewing times are usually after midnight, when Earth is turning into the debris stream.Also read | Paralvinella hessleri: The deep-sea worm that fights poison with poison, and shines like gold